Musings: Is the publishing industry a scam? Is it truly possible to be mindful? Why nostalgia feels like a lie.

A Meditation on the Business of Art, Creativity, and Capitalism

I’ve been writing a new book.

[This is not about that book.]

It’s a book about creativity and all the ways every single person is innately creative, and how accessing and harnessing that creativity will do nothing else other than better our lives and the lives of others. So, I’ve been thinking a lot about creativity in all its forms.

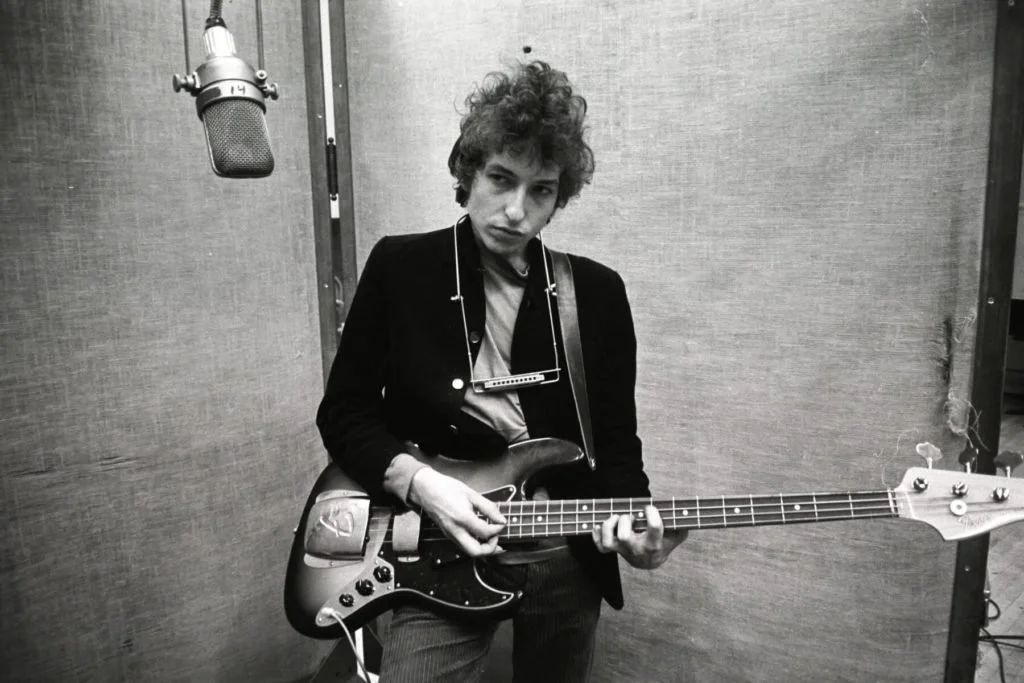

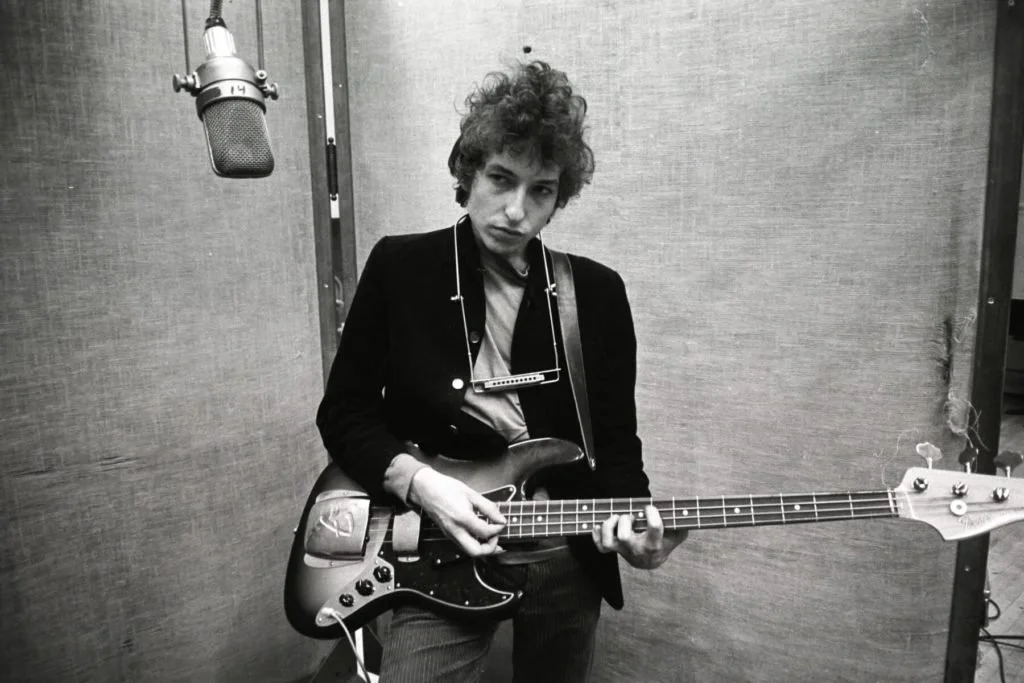

This weekend, I took a break from writing one evening to watch A Complete Unknown, the Bob Dylan biopic, and it transported me back to a different time in my life. A time when the future seemed ever-receding but always readily available to me. And it congealed a lot of scattered thoughts I’d been having around artistry and publishing and the state of our society into one cogent question: is the publishing industry a scam?

Facebook launched the year I graduated high school, and didn’t become mainstream for years after that. There was no Instagram, no TikTok, and though the internet existed, my generation only used it in the most utilitarian of ways.

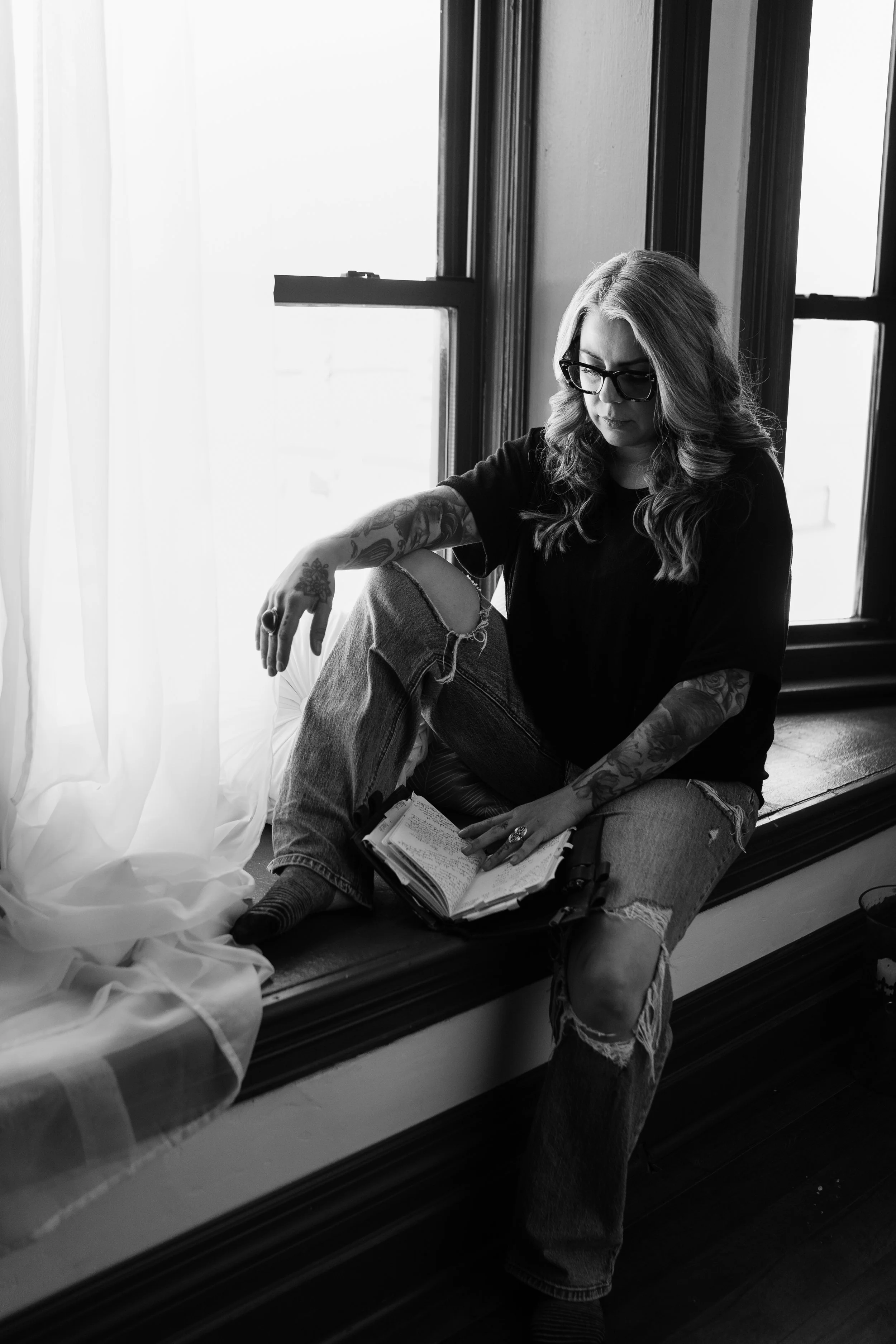

While in college in Chicago, I didn’t have a smart phone to scroll through. I walked through the city gardens to kill time, I wrote flash fiction by the lake, and I got lost snapping photos on a camera in city parks. I read books in window sills and dipped into blues shows. I found underground tapas and rooftop soirées. And I dreamed.

[This isn’t a critique of technology or smart phones or even what the internet has become. I get how Boomer-ish those last two paragraphs come off, but they’re just elder millennial facts.]

There was a small group of us in the writing program at my university, with a few friends from Columbia next door sprinkled in sometimes, and we did everything together, but most of all, we wrote. A lot. Contemporary beatniks, five guys and a girl with a creative pact vibrating on another dimension that felt like an intellectual levitation. Trotting back to our city apartment—three of us and my dog shoved into a two bedroom, eating ramen and downing PBR for breakfast, scribbling notes on grocery receipts, reciting poetry over eggs, arguing about philosophy with burning cigarettes in-hand, scratching notes on the train. We were as close as it gets to that raw ether of life—that border between survival and the “real world” to come that’s made of silt; a place I can only know in memory and never again in reality now with two small children in the suburbs. But that place was magic. We were the Bloomsbury group of our time, and our hearts were filled with anticipation of all the things we thought—we knew—were coming on the other side of graduation. We were boiling with ambition, with capital T Truth, with the literary chops to fend for ourselves against eons of prose. We were next. We thought we were next. All together. Coming up. Something special.

We are fourteen years out since graduation, and watching Bob Dylan portrayed as some strange and unusual vagabond who slipped into fame with virtually a single hurdle inspired some thoughts for me.

First. This is a peak example of how creativity winds its way into our lives without us having to do anything at all and inspires new thoughts, reflections, dreams. Watching someone else’s creativity, allowing the vibration of their work to affect us; transport us—that’s the power of creativity that is available to everyone.

I listened to countless hours of Bob Dylan on my headphones while riding the CTA. My best friend in Chicago was a Dylanite, if there is such a thing, so hearing those songs swept me away back to the Windy City, to a time when we all wondered what it was going to be like once we all had big book deals—which is to say, when we would all be voices in larger societal conversations.

But there have been hurdles. Big ones.

According to Hollywood’s portrayal, Dylan’s biggest hurdle was convincing the record label that his original music would sell, but they insisted he prove himself by first releasing an album of cover songs. But it was his persistence that proved right—that proved his own music could deeply move people.

On its face, that’s inspiring. In a vacuum, that makes me want to go shout about my own work, because it tells me that maybe if I shout loud enough that I can matter, too.

[Insert eyeroll here. Insert frustration here. Insert the inertia of reality smacking us all in the face like a pie here.]

I’m not afraid to tackle industry hurdles. I’m used to jumping through hoops, but the hoops are more complicated now than in Dylan’s era. In the age of social media and mass global dissemination of the arts, we still face the same creative hurdles now. Just multiplied by a gajillion. But like Johnny Cash tells Dylan, “Track some mud on the carpet.”

The question becomes: what are we seeking anyway?

What began as a seemingly attainable dream has become a triathlon without any real tangible goal posts. We all came up dreaming about the world of publishing, fantasizing about the lives of our favorite authors, about people reading our own little scribbled stories, and it all seemed accessible because surely publishers were thirsty for talent, for nuance, for writers who could push us into the next literary age… Surely…

I’ll try not to revisit the cliché that I’ve been born in the wrong time—that somehow life would have been different for me, actualized, in a past era—but the stark truth of the matter is that the modern publishing industry is exactly zero percent what you dreamed about as a youth. Let us first tackle the biggest and most disparaging truth about publishing.

1. Money is God and your talent and creative ideas will always come second (or third or fourth) to a publisher’s bottom dollar.

I spent so much time admiring the courage of modernist writers to explore stream of consciousness narratives that seemed wholly unnatural. For the way they dismantled the need for traditional plot structure. And the way they used stories as their protest. The looming question in our circles then was always about postmodernism: Had it already happened? Were we in it or was it past? And if it was past, buried with all its experimental flourishes, what age was developing now? Essentially, who are we as writers?

And while the answers to those questions still matter a great deal to me, they unfortunately do not matter to the publishing industry, for it is a capitalist machine devoid of concern for the legacy of literature itself. Instead, big publishing is analyzing market trends instead of technique, sales projections instead of new voices. And the modern canon of literature has fallen prey to this corporatization of traditional publishing.

Your experimental novel? Too over people’s heads. Your sweeping multi-generational meditation on sisterhood? Doesn’t cater to the public’s short attention span. Think you’re the next David Foster Wallace? Here’s a real dose of infinite jest.

2. The market is beyond saturated. It is sopping without any discernment, while simultaneously being scrupulously gatekept. Again, money.

Literary agents are beholden to what will sell and what has marketability. It’s become a strange paradox: there are innumerable options to select from in every genre, a book for every niche, every fantasy, every subculture, every reader—which, in many ways, is a lovely problem to have and a reflection of the cultural importance of literature—while at the same time, the ability to traditionally break into the market as an author is barred by gatekeepers with varying rules. I spied a very popular literary agent—she-who-shall-not-be-named—post a video that explained word count and book length is about printing cost and very explicitly told her followers that the majority of them are “not an exception to the rule.” Is this the pursuit of great art? Of literature that changes people?

As a result of all this, we see a lot of repetition in titles. A lot of copycat authors. A lot of market trends being chased by aspiring writers (re: jumping on the Game of Thrones spinoff bandwagon, or the boom of Twilight fan fic), rather than challenging new texts that progress the canon. I’ve often seen bookstagram and booktok encouraging burgeoning writers to study market trends and “write what sells.” Is it more important to be a creative writer and to spread your authentic prose on the page or is it more important to simply be a published author? Have we lost sight as writers?

3. Indie and self-publishing are the future, but they suffer from a big PR problem. Again, money.

These are the spaces that offer you the freedom to write in fresh and exciting ways and to introduce your ingenuity like no one else can. These are the spaces where you can foster your craft and your artistry without compromising your heart. And it’s important that we begin to turn the tides on big publishing and push for liberation from the drive to become celebrity authors.

Indie and self-publishing carry a stigma. I hear it in people’s reactions to them all the time. But the truth is that the success of many self-publishers has deeply affected the way big publishing operates. To save you a deep dive of the details, suffice it to say that big publishing has adapted its processes because self-publishers have proven there can be a lot of money in striking out on your own. And big publishing notices where the money goes. And while you sacrifice big advances and bigger marketing teams when taking the indie route, you gain meaningful and personalized support. Many of my favorite indie presses boast long lists of prestigious award-winning authors with important literary reputations, and those are the writers I want to stand with.

Big publishing is a victim of a larger cultural problem, of the collapse of late-stage capitalism, of the era of instant gratification, of the fast-paced and overstimulating hustle culture that fuels our need for escapism and dulls our desire for critical thinking. It suffers the same way we struggle to find peaceful mindfulness; distractionless quiet moments. It has become a merciless machine that often fights against its own allies.

My intention here has not been to put you off from publishing, though I understand what I’ve shared might feel quite daunting. Rather I hope it fills you with a zestful desire for a more dynamic future for literature, for art, for writing with Truth and authenticity and grit that isn’t typecasted or pre-packaged. Storytelling that doesn’t try to fit the next big PR campaign, that doesn’t confine itself to the molds of sects of readership, that isn’t afraid to ask big, scary questions of its readers. I want you to want books that light you up in ways you didn’t know you needed, and that leave you undeniably changed. And I want you to be able to find those books more often than not. We shouldn’t be building TBR piles where 8/10 titles are following a script of expectations. We should be equally enthralled and confused and challenged and changed by each book we open.

Ultimately, this is a toast to my community. To your unbroken creative spirits. To the Bloomsbury of the new ‘20s. To the beatniks of Gen Z. Let us find ourselves inside the writing. Let us discover a new world in the quiet moments on the page, in the tough moments, in the grit of literary discourse and the way it builds you up, turns you out, makes you reshape yourself into who you truly are and want to be. Here’s to demanding better, to leading the charge of a new vision of publishing, and to demanding that the culture value it all the same. Because without art, without writers, without our ability to turn life inside out and pour it over the page; our ability to make you look up from a sentence and sit in a mindful moment where you can hear the buzz of time rotating around the idea you’ve been left to chew on, who will contextualize the times we live in? We are the interpreters of the present moment, and in such a time as this we are gravely needed.

So go track some mud on the carpet.

In the deep hibernation of December and January, I have been creating. I have been channeling all of these things around me into workshops and programs and talks and paintings and weavings and drawings and poems. My hands have been busy in communication with my heart with the knowledge that under the threat of an ethnostate, the mere act of creativity is political resistance.